19C RAM Singers on Stage and Platform

In looking through playbills and reviews of the UK musical scene in the mid- to late nineteenth century, it always amazes me just how often names connected with RAM crop up. Of course, given that the Academy was until 1882 the only college in the country turning out professional performers, it’s not entirely to be wondered at; but this is also testament not just to the performers themselves, but to the extraordinary teachers that the institution managed to procure throughout even the first decades of its existence.

I’ve written before about just how many women at this time were able to earn a living through music, most through piano and/or singing (organ came only slightly later). From mid-century, being a former student of the Academy certainly became a selling point in the many advertisements for teaching services. There was often mention in these of specific teachers as well, demonstrating just how much these musicians were household names.

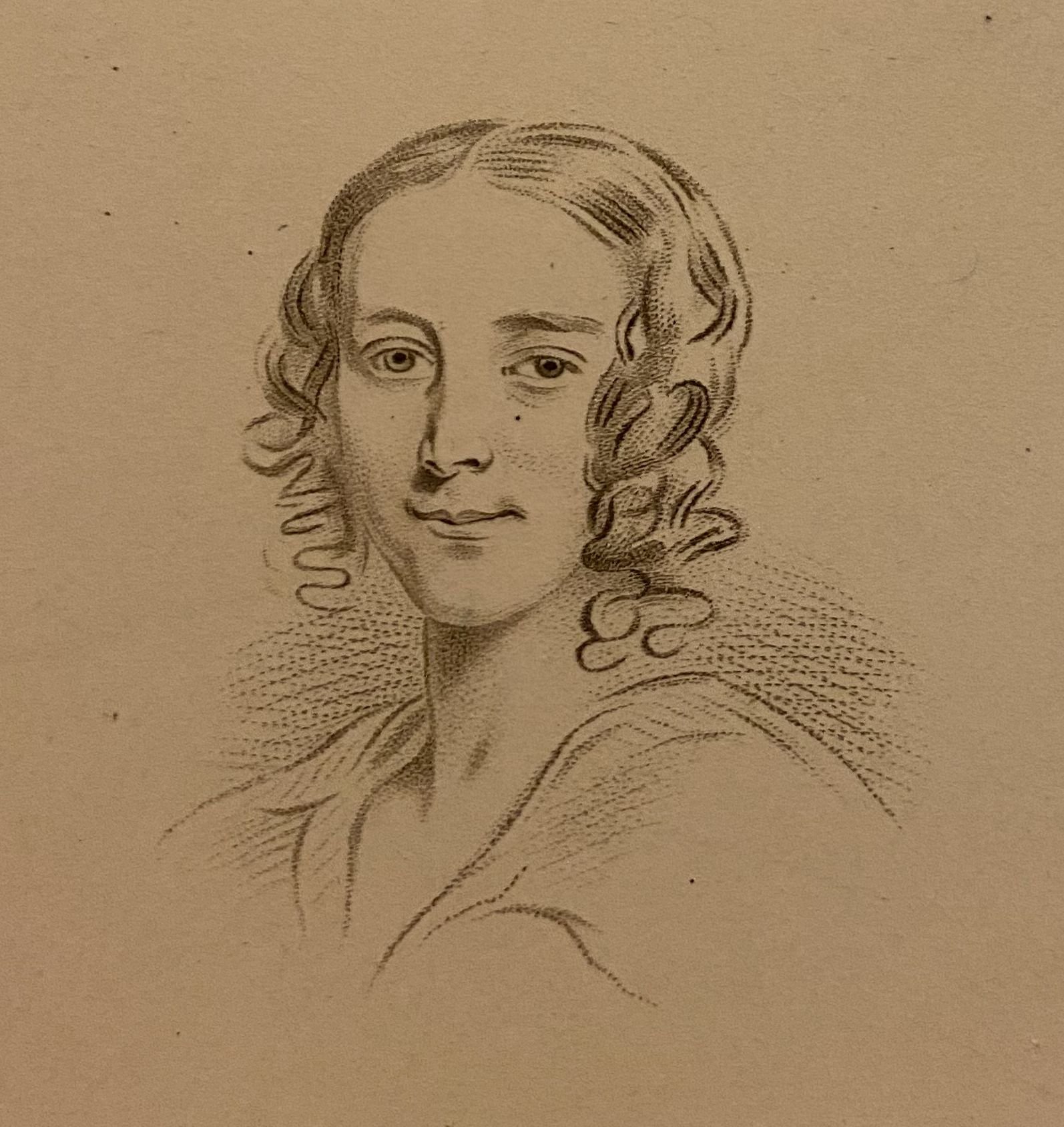

Many women also became performers, both nationally and internationally. One of the first, in just the second intake of students, was Fanny Dickens (1810-1848), whose career was cut short by her early death from tuberculosis at the age of 38. She had been known throughout the UK especially for the concerts she gave with her husband Henry Burnett, also a singer. (It might be added here that it can be quite difficult to unearth anything about Fanny – a search of archives tends to produce results pertaining to her younger brother, who wrote some books.) Two years after the beginning of Dickens’s studentship came Anna Bishop, who has already featured on this website. She was one of the most-travelled singers of the nineteenth century, sallying forth on horse cart, train, ship, or whatever mode of transport would get her to where she was going, on any continent or island. But more importantly, she was clearly a singer of wide-ranging talents, with a repertoire that encompassed opera and concert works from Balfe and Bishop (her first husband) to Handel, Mozart and Beethoven, to Italian composers such as Donizetti and Bellini. Bishop was contemporaneous with the rather less flamboyant but equally successful Mary Shaw (1814-1876), contralto advocate of both Rossini and the modern composer Giuseppe Verdi. She was another singer who benefitted from Mendelssohn’s enthusiasm for British singers, appearing at the Leipzig Gewandhaus several times.

The 1830s began with the admission of such figures as Charlotte Birch (c1815-1901). Active particularly on the oratorio circuit, she entered seven years before her younger sister Eliza Ann (1825-1862), for whom she was the recommender. Charlotte was more in demand than her entry in the 1900 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians intimated:

“Miss Birch possessed a beautiful soprano voice, rich, clear, and mellow, and was a good musician, but her extremely cold and inanimate manner and want of dramatic feeling greatly marred the effect of her singing.”

Sadly, her career was cut short by encroaching deafness, though she remained living with her sister, as so many women of this time did, teaching singing from their residence in Baker Street. Eliza roamed further afield, travelling to other cities to give occasional classes and masterclasses.

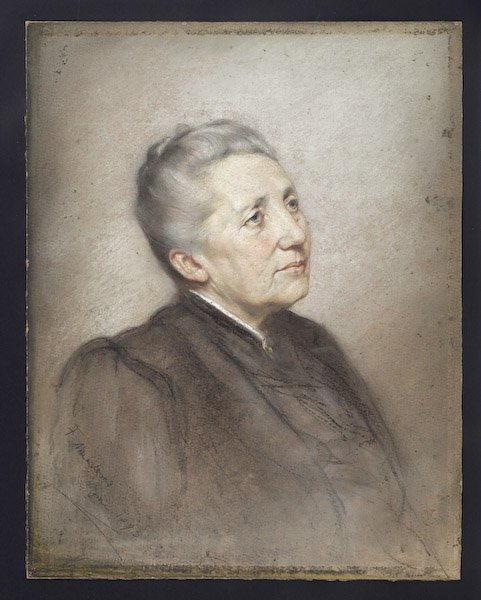

Charlotte Dolby 1821-1885 was another famous figure well into the later century, and has also been a highlight of these pages, over on Composer of the Month. Like many of the singers mentioned above, her singing career gave way to other enterprises in later life, though her name remained a drawcard for her pupils.

By the 1860s, female students far outnumbered male, and the proliferation of successful musicians amongst their numbers continued apace. Singers such as Edith Wynne,

Mary Davies, Rebecca Jewell and Arabella Smyth, to name but a few, made their name both within the walls of the Academy and on concert platforms throughout the country. Next month we will look at the change in instrument availability that resulted in a much broader impact for women in the profession.

Oboe and trumpet, anyone?…

How we listen: Contemporary v 19C audiences, with a stop in between

Myra Hess plays in a National Gallery concert during WWII

Concert Etiquette. Hands up who “gets” it?... Hands up who just gets confused?... Oh, just me then.

Seriously though, there’s a whole thing around how to behave in concerts that I have never quite got my head around, mainly because I’m terrible at sitting still. I had a conversation with a pianist once, who had just done a recital in the Wigmore Hall. He complained about the audience member in the front row who appeared to read a book the whole way through the event. If she was going to pay so little attention, he grumbled, couldn’t she just have stayed home?

Now, while sitting in the front row to read your book is perhaps a whole issue in itself, I can well imagine that she might possibly be the kind of listener who actually pays more attention, not less, through the lens of her book. While I might not want to read in a concert, I would have to confess to being an inveterate doodler/drawer/crocheter. If my hands are engaged, so is my mind and so are my ears. The way concert etiquette works, though, I only do this if I can do so undetected. I am well aware that this is seen as impolite to both performers (you’re not paying enough of the right kind of attention) and other members of the audience (you’re being distracting). Thanks, Hanslick. Maybe we should start splitting concert halls like weddings: “Good evening, madam, which side would you like? The sitting still side, or the doodlers? Right this way, follow me.”

Having said all that, it has been more and more in my consciousness just what it means for composer, performers and listeners that ways of listening have changed so much, even for the most traditionalist of concertgoers, and just how much, therefore, we ask of audiences. Even one hundred years ago, the only way of hearing music for most people – at least, music played by others – was to hear it live and in its entirety. Filing into a hall where people sat in serried rows and just listened was par for the course, if you liked that sort of thing. People were accustomed to it. (I differentiate between this and listening to oneself play partly because I find musicians some of the worst at sitting still in concerts.)

Things changed slowly but surely as technology made music ever more present, until we arrive at our current culture, with its almost incessant soundtrack. It’s made an enormous difference to how we engage with music, and it has dawned on me just how much of an ask it is to expect listeners to fulfil the role of a pre-recording audience, to leave their 21st-century ears and thought processes at the door. For some, this is second nature. For others, it is a struggle that can’t be won, no matter their relationship with the music itself. I mentioned Eduard Hanslick above, that proponent of “active” listening over “passive” listening, who did little to disguise his contempt for people who might simply let music wash over them in a wave of sensory enjoyment. He would have hated lift music.

E. M Forster wrote beautifully of what an audience really is, as opposed to what it’s assumed to be. He has just been to one Myra Hess’s National Gallery concerts that happened almost weekly throughout WWII:

“There is no such person as the average concert-goer, and no one can speak in his name. Not only does our enjoyment of music differ, but our attention wanders from it in different directions, and returns to it at different angles; so that if the soul of an audience could be photographed it would resemble a flight of scattering dipping birds, who belong neither to the air nor the water nor the earth. In theory the audience is a solid slab, provided with a single pair of enormous ears, which listen, and with a pair of hands, which clap. Actually it is that elusive scattering flight of winged creatures, darting around, and spending much of its time where it shouldn’t, thinking now “how lovely!”, now “my foot’s gone to sleep”, and passing in the beat of a bar from “there’s Beethoven back in C Minor again!” to “did I turn the gas off?” or “I do think he might have shaved”. Meanwhile Beethoven persists, Beethoven does not flicker, Beethoven plays himself through. Applause. The piano is closed, the instruments re-enter their cases, the audience disperses more widely, the concert is over.”

Christiane Tewinkel has also written about internal distraction being far more important in analysing a listening experience than is external distraction (“Everybody in the Concert Hall should be Devoted Entirely to the Music”: On the Actuality of Not Listening to Music in Symphonic Concerts”, from The Oxford Handbook of Music Listening in the 19th and 20th Centuries) ; but alongside this, we need to think about the choices we make that were once deliberate and now so engrained in our everyday life that we have forgotten that they were once voluntary. Interestingly, in some of these choices we seem to have returned to nineteenth-century values. The hierarchy of genre is re-dissolving. Just as in the late nineteenth-century you could hear ballad and art song on the same platform at the same time, or explicitly programmatic music alongside the austerely formal, so now can you choose “programming” options that never would have made it onto many concert platforms of the late twentieth century. I remember one particular concert I gave with a flautist in the late 1990s, when the venue director only very reluctantly allowed us to play Schubert’s Trockne Blumen variations alongside Poulenc’s sonata (“After all, it’s not exactly great music, is it?”). Nowadays, I might even blow his mind further by playing one or two variations, perhaps separated by other works, as most of us might often choose to listen. The hegemony of the full work, a much later aesthetic conceit than is often thought, is vanishing rapidly. A nineteenth-century listener wouldn’t blink twice, being already accustomed to performer selection.

There are, though, many ways in which we have arrived at the opposite side to the pre-recording audience. I have already written of the fact that many people hear most of their music through head/earphones, and certainly the vast majority through technology. Those headphones ensure that even when we are in a room with others, our listening experience takes place in isolation. This isn’t just a psychological separation, but is also a technological one. My headphones and my device render a sound-world quite apart from yours, much more than is engendered by our different seats in a concert hall. Not only that, but the performers have vanished, too, disembodied and distant, although conversely, the sound they produce is closer than it’s ever been, pulsing straight into our covered ears. There is little pre-listening information readily available, bar the thumbnail of the often random artwork of the album cover; sometimes it’s hard even to find the name of either performer or composer, depending on the scrolling banner that a streaming service has decided fits their algorithms best. A case in point was the Dora Bright piano concerto recording that was reviewed on these pages last month. On one particular streaming service, the only search that brought up the recording was one for the [male] conductor. Composer and performer names drew a blank. The idea that liner notes might be hanging around somewhere is laughably archaic. You can often google these, but who has the time to do that very often? Our control over the time-lapse of music is completely different, too. We can choose to play a track over and over, or even start and stop within a track, skipping backwards and forwards over the phrases. We’ve become bookshop browsers, flicking through a paperback to see if we feel like committing to the longer read.

And what effect does all this have on how we approach concert-giving? Perhaps none; but it’s certainly worth being aware of the far wider range of listening habits to which we have to relate as performers. Personally, I enjoy fragmentation as well as the narrative arcs of full works. The range of choice, and the relationship between vastly different works, become programming tools that excite me. And as we return to live music making, the opportunities we have are endless. Here’s to a new era.

Women at the Academy in the mid-nineteenth century

While the first intake of female students to the Academy have disappeared into the mists of time, in the second intake, names that make it into public consciousness begin to appear. Fanny Dickens (1810-1848) is an example, entering the Academy in 1823. She studied both singing and piano, as most of the early students did, although it was singing that formed the basis of her career, piano being the side dish. She would go on to share platforms with other musicians such as her husband, Henry Burnett, German soprano Anna Schröder-Devrient, and French singer Rosalbina Caradori-Allan – until, of course, marriage and motherhood sharply curtailed her performing activities, and tuberculosis took her at the tragically early age of 38.

Another extremely famous figure was soprano Anna Bishop (1810-1884), who appeared in these pages last week. She studied at the Academy a few years after Dickens, starting on piano with Ignaz Moscheles before her extraordinary soprano voice was discovered, leading to her switch in focus. It is impossible to do justice here to Bishop’s colourful life; I am an enormous admirer of her talent, dedication and capacity for sheer hard work, and she will appear in these pages yet again later in the year. Her pianism, one infers, was not of the highest order, and thus she missed out on any of the early scholarships, such as the King’s Scholarships instated in 1834. The first two female students to win this, their musicianship now lost to the mists of time, were Catherine Halls and Louisa Hopkins. (Poor Catherine had to suffer from an inept press, who mixed up her last name with that of George Hall, one of the two male winners.)

By the next decade, female singers who had studied at the Academy were becoming well-known on the stages of the country and the world, such as Mary Shaw (1814-1876), Charlotte Sainton-Dolby (1821-1885), and Georgiana Poulter (dates unknown). Next to become known were the pianists, including the “child prodigy” Elizabeth Jonas (c1825-1877) who was “patronized by Her Royal Highness the Princess Augusta” and admitted to the Academy at the age of eleven in 1836 to study with Ignaz Moscheles and Thomas Attwood. Kate Loder (1825-1904) and Augusta Amherst Austen (1827-1877) were amongst these numbers; both also were organists who held positions in London churches. We also see the beginning of female students at the Academy who wanted to be known first as composers, rather than seeing this as an extra string to their bow. Clara Macirone (1821-1914) was one such musician. Her prolific letters to family members demonstrate that her performances were much more vehicles for her own music than they were pianistic displays. Another was Julia Woolf (1831-1893), composer of song and piano pieces, as well as an operetta, Carina, which by 1888 was “working itself into a genuine success at the Opèra Comique by reason of tuneful, if not very original, music, and chiefly and foremost by Mlle. Camille D’Arville’s artistc and fascinating singing and acting in the principal rôle,” as a contemporary review described.

Many of these women were able to sustain a good musical career, something we forget in our haste to draw them from shadows that are not as long as we might think. Those shadows do exist – Luise le Beau wrote in her autobiography of the extra-hard work that women had to take on, still to be ignored in the higher echelons of music culture. But they are not quite the shape we imagine, and they are not as all-encompassing as is often assumed, especially if we are willing to forego a cultural hierarchy that places public venues and public critical judgement at the top. Contrary to what it may seem, this can render these women even more invisible to succeeding generations – we still have a tendency for our eyes to slide over names that appear in programmes, as being available and thus not needing our help. But as any current composer will tell you, it’s the second performance that’s the hardest to procure. And why is one performance ever enough, when we are up against works with vast reception histories, of performances that occupy an entire spectrum of expertise, thus offering a rich, multi-faceted interpretation?

Of course, the style of music that many of these composers engaged with is often now seen as anachronistic. We have a deep suspicion of Victoriana, as I have already highlighted in the review of Dora Bright’s much later concerto. The complex nature of the friction between the death of Romanticism and the influence of the ‘long’ nineteenth century, coupled with a dawning discomfiture around the physical aspect of musicmaking in classical traditions, makes us wary of the unfettered sentimentality of some of this music. Indeed, sentimentality has come to be a pejorative term, not to mention at times aligned with contempt for the feminine, seen as sitting firmly in the same aesthetic. It’s a good way of dismissing all those nineteenth-century women who wrote songs to words that make us uncomfortable now. They must be “bad” composers, because the feeling they (deliberately) engender in the listener seems no longer viable.

Here’s a performance of one of Kate Loder’s piano works, Voyage Joyeux.

The first female students of the Academy

When the Academy opened in 1822, it was “for the maintenance and general instruction in music of a certain number of pupils,' not exceeding at present forty males and forty females.” The general idea was that these young musicians would be able to “enter into competition with, and rival the natives of other countries, and to provide for themselves the means of an honourable and comfortable livelihood.”

In the event, on 8 March 1822 ten girls and ten boys were admitted as the foundation students. These young people ranged in age from 10 to 15 – it is a common error in histories to believe that the Academy was always for an older generation. Unlike its rival over in Paris, however, which was there for musicians on the verge of the profession already, the Academy wanted to get in early in the educational journey. It wasn’t until well into the twentieth century that the average age rose to what it is now, i.e. tertiary age.

There are several histories of the Academy. Frederick Corder wrote the first one in celebration of the centenary, in 1922. He sets out in some tortuous detail all the meetings and ruminations leading to the opening, then finally gets to the whole point of the exercise, the students themselves, listing those first lucky twenty:

Corder, with a startling lack of imagination and social comprehension, goes on to say,

“The order in which these names are placed is according to the number of votes they obtained, and therefore according to their apparent talent at the time, for they were elected purely on their merits, Nearly all the boys distinguished themselves in after life, but not one of the girls, a fact for which I offer no explanation. ”

It would not be until the late 1830s that the female students began to make themselves more known on the platforms and publishing houses of the country, with the advent of the generation that included such names as Kate Loder, Clara Macirone and Charlotte Sainton-Dolby. It might well be noted that this generation of female students had recourse to the same teachers as the boys did, although still not quite the same range of subjects. This is not so much an indictment of the teachers the first girls had, who were perfectly well skilled in both music and education, but a reflection of the explicit assumption that girls learned music for a different purpose, one that did not include a professional career beyond the livelihood stipulated in the Academy’s first set of regulations.

Silvano Arieti’s fantastically-named book Creativity: The Magic Synthesis has a chapter dedicated to the kinds of factors that help foster creativity in artists, and the ways in which the society around them can help rather than hinder. He has a list of nine suggestions, ranging from bluntly pointing out that people not only need the tools of their trade, but a financial independence that allows them to purchase these as and when needed, to highlighting the need, in some form or another, of recognition of achievement. In amongst these factors, he points to what he calls the “interaction of significant persons” – in other words, the need for excellent teaching, mentors, collaborative projects, and all the other * of a creative community. No one creates in a vacuum, even the artist alone in an attic garret, shuffling papers off into a forgotten drawer. Allowing female students access to the same community as the males were was the first step towards allowing them entry to that community. I am reminded of Carl Friedrich Zelter’s Liedertafel in 1820s Berlin, when the men sat around a table and sang, while the women sat in an outer circle, listening. As Wilhelm Bornemann’s 1851 history described it:

“In the legends of the Round Table of the British King Arthur, or Artus [...] Queen Guinevere, Arthur’s wife, also appeared with her women. Not at the actual Round Table, but nearby in a window nook, the great noblewoman waited, keeping watch over the happy affairs of the knights and bards.”

In the community but not of it…

A look at the difference in the timetable for girls and boys is also telling – several crucial differences immediately spring out. For a start, there is less practice time for the girls, right from the beginning of the day, when boys rise half an hour earlier to fit practice around prayers and breakfast. Girls don’t get to their instruments until 9 o’clock. They also lose half a day on Wednesday. The other most obvious discrepancy is simply the sheer diversity of the boys’ exposure to musical sound – of course, there is not a whisper of a brass or woodwind instrument in the girls’ timetable. Its really not hard to see that despite those lofty words at the beginning, the Academy saw a feminine “livelihood” as rather less fraught with possibility than the masculine equivalent (and to some degree, vice versa - who could say if there were boys who longed to follow in the footsteps of harpist Nicholas-Charles Bochsa, to all evidence an inspiring teacher?).

I am also quite fascinated at the thought of “tuning taught” – I wonder what this entailed?

The foundations being laid here, however, shouldn’t be underestimated. By the time we arrive at the latter part of the century, things are becoming different, and female students were at the forefront of public Academy life, especially in the number of composers having their works performed in the Academy’s concerts. Remember Liszt’s first piano “recital”, performed in London’s leading concert venue, the Hanover Square Rooms, just around the corner from the Academy’s first site in Tenterden Street? That was the venue for many of the RAM events, and thus the site of many premieres of works by female students. How this translated into the wider music culture is a different question, of course with a much larger pool of factors, not to mention the immeasurably complex question of reception.

In February’s blog entry, we will look at some of the next generation of women who had a RAM education behind them. The mid-nineteenth century London music scene was awash with ex-RAM students - singers, pianists, teacher, composers, including one who was shipwrecked, rescued, and continued on a world tour as though it were all in a day’s work. See you all next month!

The Janusian Blog Entry

This year, I decided to dedicate the Salon Without Boundaries social media presence to birthdays of women composers. Over three platforms, we have celebrated the birth of 1,405 composers, never missing a day. We covered women from the sixteenth century to the mid-twentieth - I decided to have a cutoff point of 1970, just to keep my time manageable. I found composers from all corners of the globe, from six continents – and one who at least had her music performed on the seventh – and in so doing, I earned far more than I had imagined I would, not just about the composers themselves, but also about the worlds they inhabited and the people with whom they interacted. I also learned what people are interested in today, sometimes to my surprise!

Of course, there are many, many composers whose exact date of birth is unknown, and some of these will be celebrated in the Salon throughout 2022. The Salon’s social media presence will be a little less this year, as we concentrate on building website content, not to mention rebuilding a real-world musical life after the ravages of the past two years. Still, on both website and SM we will be marking the bicentenary of The Royal Academy of Music in London. Founded in 1822, the Academy’s premise was to provide musical education to young teenagers:

“The object of the Institution, under His Majesty’s patronage, is to promote the cultivation of the science of Music, and afford facilities for attaining perfection in it, by assisting with general instruction the natives of this country, and thus enabling those who pursue this delightful branch of the fine arts to enter into competition with, and rival the natives of other countries, and to provide for themselves the means of an honourable and comfortable livelihood.

With this view it is proposed to found an academy, to be called the “Royal Academy of Music”, for the maintenance and general instruction in music of a certain number of pupils, not exceeding at present forty males and forty females.”

We have an upcoming blog entry devoted to the differences in provision for boys and girls, so we won’t go into that here; we can, despite this, acknowledge that the Academy was ahead of its time in allowing instruction at all to both sexes; its geographically closest equivalent, the Paris Conservatoire, would not admit its first female student until the nine-year-old violinist Camilla Urso entered in 1849. And later in the century, female composers would choose the Academy over its rival institution across London, because of its policy of playing student compositions in every concert, by both male and female composers. This would change around WW1, when the Royal College of Music became the preferred institution for many, due in large part to the stellar teaching staff in the department there. Meanwhile, however, Academy prizes were just as likely to be won by female students as by male, and the prize boards often read like a rollcall of the best composers of the time.

The Academy was one of the first to allow its girls to learn instruments other than the traditionally female singing and piano. In the 1890s there were more female violinists than male, and in 1901 there was at least one female cornet player, Catherine Fidler. This was also the year in which Maude Melliar became the first female winner of a wind instrument scholarship in the UK. Edith Penville on flute followed closely behind. And despite the perceived ‘femininity’ of the piano as an instrument, the sheer weight of talent amongst the women pianists at this time was phenomenal. The singers, too, offered an extraordinary raft of talent and achievement, and it is not an exaggeration to note that the majority of successful productions in London included at least one Academy-trained voice.

Over 2022, we will be celebrating many of these women. All Composers of the Month were trained at the Academy; we will also have a cornucopia of recordings of works by other composers. Even the books will be by ex-students of the Academy, starting with one by a well-known pianist. We look forward to sharing these with you. Please continue visiting us throughout the year for more!