Dora Bright 1862-1951

I have often wondered what would happen if a traveller from another planet landed in the midst of a group of musicians talking over their music-making of the past week. Listening in, our intrepid traveller might hear snippets of conversations that included a lament that the Mozart had proved tricky in the practice room yesterday, or how great it had been to dep in the Mozart, or the Mozart was expensive to buy. Someone might even leave for a few minutes, having realised that they had left the Mozart in the band room. Our traveller might be forgiven for wondering what this Mozart is, that it moves around so much, provides much bother, and features in so many people’s lives at the same time.

I use a male composer on purpose here, because this rupture that we create between the composer-as-composer and the composer-as-person seems to me writ extra-large by its absence when it comes to women. The composer-as-composer is a concept, synonymous with the music that eventuates from its existence (as has been written about by many philosophers). We can only think this of music that is seen to rise above its purpose, and thus much music, particularly that of women, fails at the first hurdle of sublimity. Music always has a function – to be performed and heard, i.e. to be a communicative tool of people – and I believe that much music by women makes this explicit in ways that are uncomfortable to our lofty assumption that great music exists in and of itself.

Why do I start with this? It’s because Dora Bright, the subject of today’s offering, was extremely well-known during her lifetime, both as composer and as pianist, yet fell almost completely into oblivion after her death. It feels to me that quite apart from her sex, and the issues surrounding accessibility of the music (an enormous problem for Bright, much of whose music remains in manuscript), this is also in part an outcome of the “functionality” of her music, of its close ties to performance. I’m looking forward to the book on her life coming out next year (authored by Anthony Bilton), but in the meantime, here is a short version of her varied and busy life.

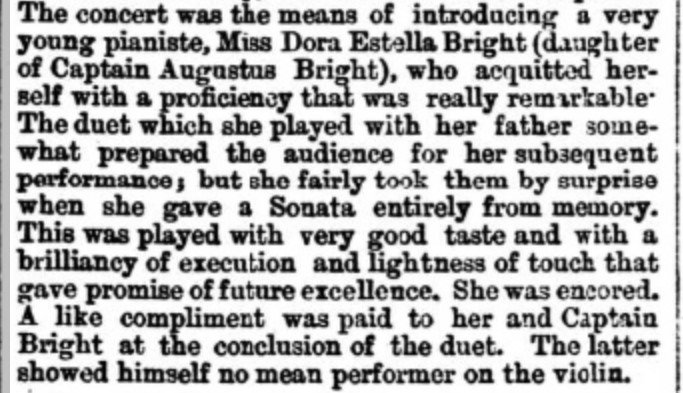

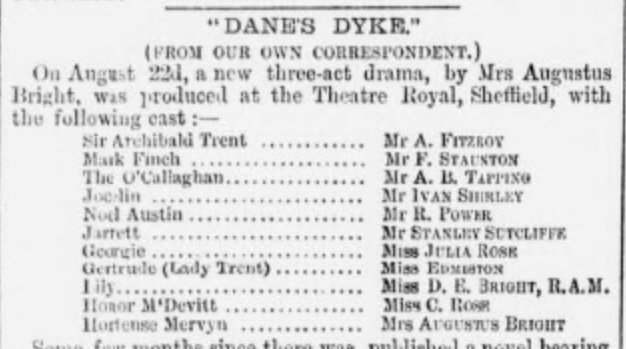

Dora Estella Bright was born in Yorkshire on 16 August 1862 to Katherine Coveney Pitt, an actor, writer and theatre manager, and Augustus Bright, a merchant. Katherine’s love of the theatre was clearly passed on to her daughter, who would go on to write music for plays and ballets, while Augustus offered a love of and talent for music. Father and 9yo daughter united in a benefit concert in 1873, “for the purpose of increasing the sick fund of the band of the Hallamshire Rifles”, playing violin and piano duos by De Beriot and Benedict (Dora also played a solo Beethoven sonata). 8 years later in 1881, Dora would share a stage with her mother in a production of Dane’s Dyke, an adaptation of one of Pitt’s own novels, at the Theatre Royal in Sheffield.

Two years later, however, Bright chose music over acting and decided to concentrate on the Royal Academy of Music. Here she had a stellar journey, studying with Walter MacFarren and Ebenezer Prout, and winning several of the top prizes. I have already spoken elsewhere of the importance of access to the best teachers, and these two names, much less known today, demonstrate that by the fifth decade of its existence, the Academy was allowing girls lessons with the best. (It’s a sad indictment of our priorities, that the names of talented teachers are often lost to time.) Her prizes included the Charles Lucas Prize for composition, a Potter Exhibition, the Lady Goldschmid scholarship, and the Sterndale Bennett prize for piano.

Bright was enormously successful as both pianist and composer at the Academy, and alongside winning prizes, she performed and had works played in RAM concerts, including in fron of Liszt during his 1886 visit. She was also becoming known further afield especially as a pianist, being noted for her ‘remarkable skill’ and ‘promising career’. Her own works featured often in these concerts around the UK, such as the Theme and Variations on a Theme of George MacFarren for piano duo, in which fellow RAM composer Ethel Boyce would join her at the keyboard. Her time at RAM culminated in a performance of her first piano concerto, just before she left the institution. This gained high praise from around the globe, reaching as far afield as Australia. Reviews closer to home were positive, if somewhat gendered in their approach:

“There are fresh and graceful ideas belonging unquestionably to [Bright], and the instrumentation, although not strong, is picturesque and well blended with the solo instrument. The first movement is, perhaps, the least decided in style, but the second intermezzo has some beautiful passages, in which the combination of the pianoforte with the strings indicates an excellent feeling for composition and tone painting. This was loudly applauded, and in the finale there were some clever and effective ideas. ”

The concerto was a popular addition to programmes for some years, and was heard in Germany during her concert tours there in 1889, 1890 and 1892 (indeed, there is no evidence of any other pianist every playing it, making Ward perhaps the second ever, with this recording).

Just after this third tour, Bright married Wyndham Knatchbull, thus setting in motion the inevitable slide into oblivion that was the * of so many nineteenth-century women who composed publicly. It was an odd union, the military Kntachbull being forty years Bright’s senior, but surely financial stability and an abiding sense of community were part of the draw, as the couple settled at Knatchbull’s estate in Babington, Somerset, where Bright immediately took over much of the running of the local amateur music scene. The Babington Strollers, under her leadership, became renowned for their productions of Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and she also brought in illustrious musicians from her wider network in a series of concerts and recitals in which she herself played to glowing reviews:

“Miss Dora Fellowes earned the cordial applause of the andicnce for her admirable playing of solo on the violin ; while rich treat was afforded by the pianoforte playing of Miss Dora Bright (Mrs. Knatchbull), whose recitals on the instrument mentioned are of sufficient note to attract large metropolitan audiences. This portion of tbe programme was thoroughly appreciated and bad time permitted the audience would have hod tbe ptincipal features repeated.”

Married life was shortlived, as Knatchbull died in 1900. Bright returned to composing, particularly for her extremely successful collaboration with the dancer Adeline Genée. Some of the resulting ballets – or “dance plays”, as some reviewers called them – ran for several seasons, such as The Dryad (on the story by Hans Christian Andersen), La Camargo and La danse, the last of which premiered at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Other works also followed, including a Suite bretonne which was performed by flautist Albert Fransella and the New Queen’s Hall Orchestra at the Proms in 1917, under the baton of Sir Henry Wood. Her involvement with her local community through music and charity continued until her death at the age of 90 in 1951.

Bright’s catalogue of works is enormous, ranging from song to stage and orchestral works. Why has she vanished so completely from our musical consciousness? (That’s a rhetorical and slightly cynical question, by the way.) Of course, the absence of the majority of her manuscripts and therefore of printed scores is the biggest obstacle at least to the current performance of her works, but this does not excuse, or indeed explain, the veil erected between her story and now. Our obsession with seeing a printed score as the ultimate sign of musical authority, particularly an authority that lasts across time, does enormous injustice to vast swathes of past musical landscapes.

Have a listen to the beautiful Intermezzo from the first concerto, performed by Samantha Ward with Charles Peebles conducting the Royal Liverpool Philhramonic Orchestra.