Agnes Zimmermann 1847-1925: The London Clara Schumann

There are very few photographs of Agnes Zimmermann that remain in the public arena, and the few that do exist are from her young years (I have the feeling that Agnes was a very private person - her will stipulated that the portraits of her parents should be burned, along with other documents and photographs). These were decades in which carefully complicated hair styles abounded, and corsets were required at all times in public, both hair and body being tamed into submission. It is the first thing I see when I look at these photos: tumultuous and thick hair curled and pulled and plaited, the curve of the tightly buttoned dress that alludes to the corset beneath. Many years ago, I played a concert dressed in long gown and corset. I doubt the strings were pulled anywhere near as tightly as Zimmermann’s would have been, but still, the impossibility of free movement at the keyboard was more than impressed upon me, as was the realization that I could never be entirely focussed on the music as long as I was wondering how to take my next breath. My admiration for these women, who had to perform with physical handicaps applied that no man could even dream of, was enormous.

Zimmermann was an extraordinary cultural figure, and I often wonder if that plait down her back was a visual sign of quiet rebellion. She did not fit the mold even of the Macirones and Dolbys of the generation before her, women who also refused roles thrust upon them, and carved their own paths; pianist, teacher, traveller, editor, composer, adjudicator, concert organiser, saloniére, dedicatee, like Clara Schumann over in Germany (the country of Zimmermann’s birth), Zimmermann’s influence was broader and much greater than her post-life reputation would demonstrate.

Although Agnes Zimmermann was born in Cologne, Germany, she spent the majority of her life based in London. She had started playing the piano at 5 years of age, with her only instructors being “her father and a poor German, whose capabilities were confessed of the meagrest order”, as an 1857 review claimed. Within a few short months she had learned a plethora of music and technical exercises, whereupon the family moved in England in search of better tuition. They lived first in Hastings, where the young Agnes studied first with Wilhelm Kloss, a well-known piano teacher and composer. It was only a few months later that she gained a place at the Royal Academy of Music to study with Charles Steggall and the principal, Cipriani Potter. She was just nine years old.

Zimmermann appeared in public from just weeks after her arrival in Britain. The public, always fascinated by infant prodigies, welcomed her with open arms (although it seems as though a year was sliced off her age for the benefit of the newspapers). Reviews were glowing:

“The most distinguished characteristic of Mlle. Zimmermann’s playing is great energy, and an instant comprehension of her subject; an energy which carries her over every obstacle, and a comprehension that fathoms the profoundest depths of the musical art; in a word her genius seems unlimited.”

Life inside the Academy was equally successful, with Zimmermann winning the King’s Scholarship from 1860-62. Her studentship ceased in 1864, a year after a successful appearance at the Crystal Palace concerts playing Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto, the first of many that would position her not only as a fine pianist, but as a proponent of what was becoming the mainstream canon of piano works, especially the “classics”, as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven were already being categorised. She remained a busy performer for several decadesundertaking several European tours, mainly throughout Germany, as well as being well-known throughout the UK. She gave a long-running concert series at the Hanover Square Rooms, haunt of many an Academy student, as well as at St James’s Hall. She was associated with the Philharmonic Society, performed regularly at the Monday Popular Concerts and at Crystal Palace. She was a frequent chamber music collaborator, sharing a platform with violinist Josef Joachim and cellists Franz Xaver Neruda and Alfredo Piatti.

Zimmermann would continue to give concerts, both public and private, until the year before she died. She continued to be known as a champion of tradition and classically “clean” playing. In 1904, she was included in The Gentlewoman in their Roll of Honour for Women: “Under this heading shall be given from week to week interesting biographical details, all specially written, with portraits. of English-speaking women who have achieved distinction in work for the public good, or in the arts and professions. Position in the social world, often the mere accident of birth, does not entitle to inclusion in Roll of Honour, its object being to tell something of the strenuous lives of those who work to further objects of usefulness to the State or Individual.”

Her dedication to earlier forms and ways of music making were evident through her other musical activities, from the composing to the adjudicating and editing. Her Beethoven and Mozart complete sonata editions were published at a time when women editors were still an anomaly, but they certainly attracted an eye-wateringly high price tag:

There is little in Zimmermann’s own words, but this summation of her adjudication at the 1904 Feis Coeil gives a sense of what was artistically important to her:

“The pieces in the senior grade were admirably calculated to test the capabilities of the players; many of them acquitted themselves extremely well. In most cases the Bach Prelude was rendered with complete accuracy, while in the Fugue the subject was well defined and clearly brought out. Yes, on the whole, the work was regarded somewhat in the light of a mere mechanical exercise, and few appeared to find any beauty or musical meaning in it. […] In the Beethoven Adagio, the melody was not always sufficiently well sustained, and there was a regrettable tendency to ignore rests, resulting in the breaking of time and rhythm. […] The best achievements were certainly in the concerted music, many of the performances being exceedingly good. The various works had been studied with great care and insight, and they were played with spirit, feeling, and due attention to light and shade.”

Of course, the other large and continuous strand of Zimmermann’s musical life was composing. Her compositions were performed in Academy concerts during her studentship, and she went on to publish a considerable number of works. Like many women before her, she knew what sold, and it was the solo and four-part songs that contribute the majority of publications over her lifetime, although her chamber music, including the solo piano music, also appear in the earlier decades. These convey her fascination with traditional form, from the three piano and violin sonatas, to the piano fugues, all of which exhibit the same combination of craftsmanship and musical voice. We will be talking more about this side of Zimmermann next week when I review a recording of her violin sonatas

Music was only a part of the colourful life of Agnes Zimmermann. She was a devout Roman Catholic who was active in the church, and a supporter of women’s suffrage, being a member of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. Over the last years of the nineteenth-century, and first decade of the twentieth, she also took a lengthy break from high-level public life, living with the philanthropist and education activist Louisa Lady Goldsmid until the latter’s death in 1908. Lady Arbuthnot’s obituary of Zimmermann, written in 1926, noted that:

“Though Miss Zimmerman’s public career was a good deal interrupted for 18 years by her devoted attention to Louisa Lady Goldsmid, whose home she shared after the death of Sir Frances Goldsmid, she never lost interest in her art, and continued to give her annual recitals for several years in succession.”

While this relationship has been the target of “speculation” (how I hate that word!) ever since, Sophie Fuller sums up its importance brilliantly:

“The facts of the devotion, the interrupted career, and the shared home remain a powerful reminder that women’s varied relationships with each other have always played a vital, if often neglected, role in their histories. Despite what can seem like overwhelming attempts to show otherwise, not all women can be defined by their relationships with men and male institutions.”

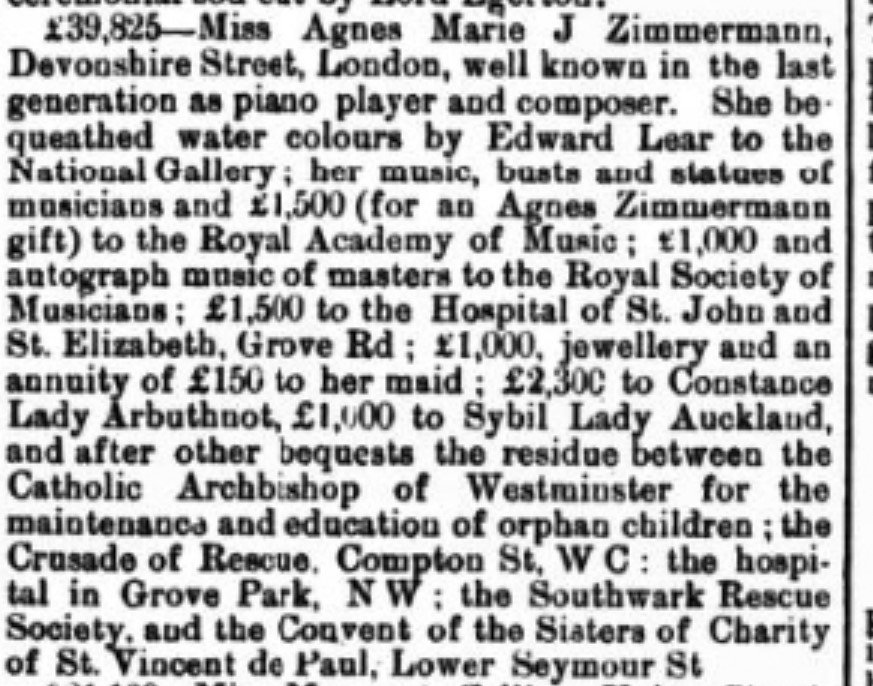

Agnes Zimmermann died on 14 November 1925 (notable as Fanny Hensel’s 120th birthday). Her considerable estate was divided amongst the many people and causes that had sustained her intellectual and cultural life for so long. It is testament to the extraordinary life she led, and the reach of her influence. Have a listen here to the introduction to her piano trio, Suite Op.19.