To Dirty for the Windmill: Caryl Brahms

Most biographies of Caryl Brahms mention the fact that she was a student at the Royal Academy of Music; or that she was “educated” there. It might feel rather a stretch to include Brahms in the back catalogue of Royal Academy of Music students, given her own feelings of ignominy around her truncated studentship – she rarely mentioned her time – but nevertheless, a student she was, and her months at the Academy were part and parcel of the colourful and extremely varied background that influenced her writing. Certainly she never strayed far from music as an art. (And just because I am a pedant, it’s worth pointing out that until 1990, students didn’t “graduate” from the Academy in any case – they were awarded medals for attaining a certain level after a year or more.)

Too Dirty for the Windmill is a suitably multi-faceted volume. It’s autobiographical, but not an autobiography, at least in the sensibly time-ordered, informative sense of the mainstream genre. It is written as a life-under-construction, as Caroline Heilbrun’s living in advance of writing. Ned Sherrin, one of Brahms’s collaborators, has collected fragments of her writing, and fashioned it into what feels almost like a posthumous interview.

After a first chapter covering Brahms’s early life, Sherrin divides the book into projects rather than time spans, although maintaining a loose sense of chronology. Thus, her collaborations with S.J. Simon and Ned Sherrin himself are covered in one, as is her criticism and nonfiction writing. Wikipedia starts by saying that Caryl Brahms was “an English critic, novelist, and journalist specialising in the theatre and ballet. She also wrote film, radio and television scripts.” This does little justice to the breath of her accomplishments. Rather like an actor who can take on parts, disappearing into the character rather than acting as themselves in another costume, Brahms could match her context with her language. However, she did not always take the arts entirely as seriously as some might have wished; Hoffmann’s obeisance to Beethoven’s sublime passed her by, as this 1952 review laments:

“Newcomers to the ballet, in search of expert guidance, could do no better than read A Seat at the Ballet by Caryl Brahms […]. After explaining how ballet is a synthesis of music, choreography, painting and interpretation, Miss Brahms proceeds to give analytical descriptions of the great classical ballets and other works in the current repertoire of companies likely to be seen in London and the provinces. There are times when the author’s facetious style is ill-suited to the valuable information she wishes to impart, but enthusiasts should derive more enjoyment from the ballet after reading this attempt to disentangle the subject from its mysteries.”

This is not to say that she did not recognise the enormous importance of the arts in human existence. Even in the most satirical of her writing, one cannot mistake her passion and deep commitment. This is one such example, written “when she joined the large gallery of people connected with the arts to be painted by John Bratby”:

“Have you ever felt like an onion in the process of being peeled? Layer after layer of your hidden self exposed as the white rings are forcibly unfurled? You haven’t? Then you cannot have been painted by John Bratby, the lay-it-on-thick painter – in the civil sense – and so your experience of life will be a little less rich for that reason.

‘Would you say that Christ had charisma?’ was one of the questions shot at me while he applied a thumbful of orange paint to the canvas, when I underwent a four-hour analysis by paint and painter called ‘sitting to him’.

[…]

[Bratby] was to become unpopular with the mother-in-law of his first marriage – a sorely-tried lady, one assumes – by ‘borrowing’ her groceries and spiriting them away to paint. His painting in the thick, ‘the unnatural look of vigour in a painting’, made it imperative to demand an extra allowance of artist’s material.”

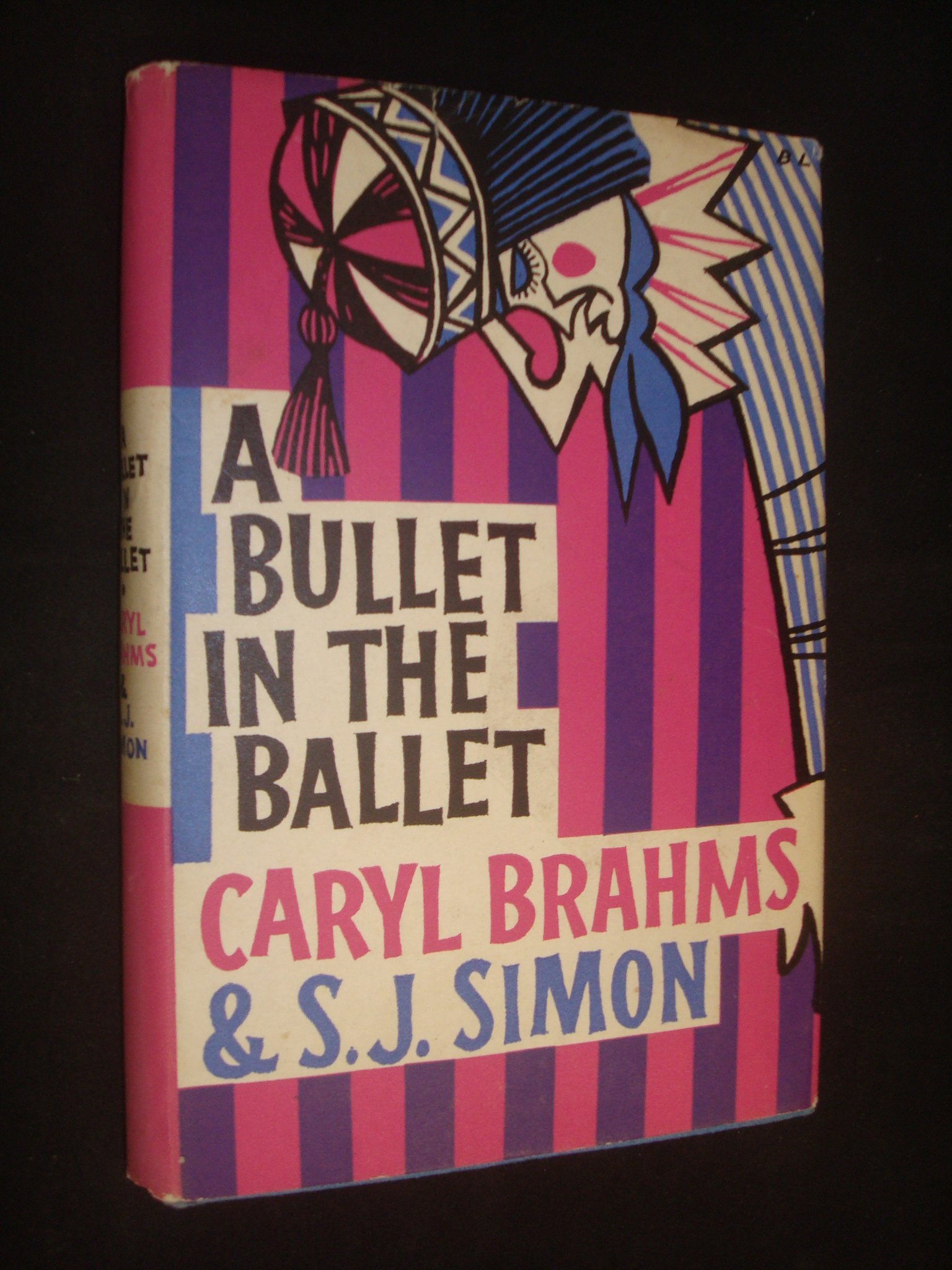

Brahms, of course, wrote both nonfiction and novels, two very different ways of writing for any author. At times these blurred, as in her imagined rewriting of the life of Mrs Siddons, but most fell either into criticism, such as her books on Gilbert and Sullivan, Chekov, and the ballet, or on the other side, into the genre of crime fiction. This latter type of writing began with A Bullet in the Ballet, written as one of her eleven-book partnership with S. J. Simon: “Skid [Brahms’s nickname for Simon] took over the detection and the love scenes, and I did the ballet bits. Together we wrote the narrative.”

It’s interesting to see how many women at this time chose to write detective novels. I see Virginia Woolf’s “woman’s sentence” as a common thread in these books, one that books by men do not share – a thread with the needle still attached, sharp, bright and true in aim. Patricia Wentworth, Ngaio Marsh, Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, Caryl Brahms, Carolyn Heilbrun, to name but a few of my favourites. What is it about the delight of constructing then unpicking this kind of puzzle, not to mention the pleasure in a bit of vicarious rage, that taboo emotion for women?

The fragmentation of the writing feels real here. It’s a book to come to and from, rather as Brahms herself did in the act of creativity. We hear Brahms in her own words, though in an ordering of Sherrin’s choosing – and much to his credit, he understands the necessary control this exerts, writing in what amounts to a dedication to his writing partner, “Dear Caryl, I hope the ‘heavy hand of Ned’ does not lie too leaden across your memories…”