Summerhayes Trio: English Romantic Trios

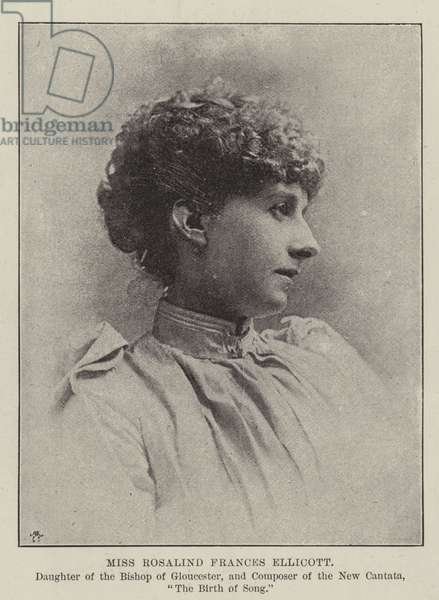

Several years ago, when we were searching for music by Academy women for a series of concerts, I remember spending quite some time attempting to uncover both scores and recordings of the chamber music of Rosalind Ellicott. Then, there was one recording that I could find – a 2005 compilation of “English Romantic Trios” by the Summerhayes Trio, which included her second trio. Finding a score was harder, but not impossible; at the time, the first trio was nowhere to be found in an accessible format, let alone any of her other many chamber works, such as the violin/cello and piano sonatas, a string quartet, various smaller, programmatic works. The state of things isn’t much different now, although Trio Anima Mundi have now made an excellent recording of the first trio on their own CD of English works (what is it about turn-of-the-century English composers that they always seem to get grouped together like this?).

The Summerhayes ensemble have a specialism in English repertoire; other albums in their catalogue include one of works by Tom Ingoldsby ,and a 2-volume collection of Alan Bush chamber works. This early CD is a collection of four premiere recordings. Ellicott’s work, the only multi-movement work on the disc, is by far the earliest, having been written in 1891 (and the fact that it’s the second rather than the first that makes it onto this disc makes me wonder if the programming is at least in part an outcome of the lack of a score of the earlier work back in 2005, when the CD was recorded). The other three are close together , with Alice Verne-Bredt’s Phantasy Trio and Dunhill’s Op.26 written in 1908, and Austin’s in 1909. All three of these later, one-movement works have the feel of Cobbett prize entries, given that two of them were explicitly titled as Phantasies, and all of them hovering around the 10-14 minute mark in length.

Calling all four “English Romantic Trios”, however, begins to feel somewhat surprising, not so much because of the dates, although those don’t help, but because the label seems to be much more to do with an assumed aesthetic than with any historical placement. At least they’ve avoided that most careless of labels, the “English Pastoral”, which Dunhill in particular has been accused of writing. It serves to underline how uneasy we are in that very specific English aesthetic on music prior to WWI. What is the connection here? The ensemble is clearly making one of musical language; another one that fascinates me for these four composers in particular is their convictions about the importance of excellence in music education, especially in the early formation of young musicians. It feels to me as though this conviction spills over into these works, offering a clarity of emotional communication and intent.

Ellicott’s trio is definitely the centrepiece of the CD. She herself felt she “wrote best for violin”, a view upheld here. Both her trios were successful in her lifetime. They both trios had multiple performances, from a range of performers that didn’t always include the composer herself (this is extremely important). One notable performance of the D minor trio took place at the Queen’s hall in 1891, with the teenage Sybil Palliser on piano, Richard Gompertz on violin, and Alfredo Piatti on cello. Palliser would go on to be a composer herself; at this point she was still a student at RAM, where the illustrious Piatti was still teaching, while Gompertz was across the park at the College. Another performance was given by Ellicott with two orchestral players who were well-known in London. The way in which this demonstrates the fundamental importance of networks of teacher/pupil, educational institutions, and generations of players is fascinating:

“The Musical Artists’ Society gave its fifty-third performance on Saturday last at the Prince’s Hall, Piccadilly, when the programme opened with a Trio on G for violin, violoncello and pianoforte by Miss Rosalind F. Ellicott, whose cantata “Elysium,” produced at the last Gloucester Festival,created such a favourable impression. The Trio, which consists of three movements, an Allegro Con Grazia, Adagio and Allegro Brilliant, is a graceful and well-developed production, and it was very sympathetically and satisfactorily played by Mr Buzian, Mr B. Albert, and the composer, Miss Ellicott being recalled to the platform upon the conclusion of the work. (1890)”

Ellicott’s work is in the standard four movements. The first, the allegro appassionato, flings the listener into the texture immediately; the intensity does not let up for the whole movement. The soaring lines of the andante sostenuto create a bridge to the upbeat Scherzo and Trio, which in turn lead to the concluding allegro molto, a return to the tumultuousness of the first movement. Ellicott’s flair for handling form and instrumental balance is evident throughout.

““I have since produced a trio in D minor for strings and piano, which is my best work yet. I write it by fits and starts as I am in the humour. I like composing for the violin best, I think. I never, however, work at night or for more than three hours at a time. I compose rapidly, and I get a whole movement in my head before I touch paper. I hardly every alter my compositions.””

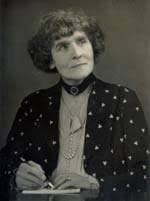

The Verne-Bredt was new to me, although the composer herself was not, belonging to a fascinating musical family that emigrated from Germany to England, accruing a few name-changes along the way. Verne-Bredt chose the anglicized version, double-barrelling it with her husband’s name. Her Phantasy Trio won a supplementary prize in the Cobbett competition, and was performed several times in the concert series she had inaugurated at the Aeolian Hall in London with her husband, William Bredt. One contemporary review comments the music moves “from gay to grave”, though the first is not the adjective I would use for the 5/4, C minor moderato opening. Although the work is technically one movement, the sections are fairly pronounced, ranging from a brief adagio doloroso to a light allegretto. Despite these frequent changes, the work is coherent and narrative.

Mention must be made of the remaining two trios on the disc, by Thomas Dunhill and Ernest Austin. These two works in fact open the programme, were one to listen to the album in its entirety. The Dunhill is less known than his later work for the same instrumentation, while Ernest Austin sometimes is wont to fall under the shadow of his more famous brother, Frederick, especially as Ernest was self-taught and thus less attached to public performance. I remember playing some of Dunhill’s myriad piano pieces for children in my early piano years; I was glad to make acquaintance with other genres.

Here is a short work, Lullaby, by Alice Verne-Bredt, played by the famed cellist May Mukle with pianist George Falkenstein in 1915.