Agnes Zimmermann: Three Violin Sonatas

On the wonderful website that is archive.org, there are three volumes of manuscripts by the pianist-composer Agnes Zimmermann. Most of the works contained in them remain unpublished – piano sonatas, fugues, quartets, part songs, and a piano-wind quintet. They are fair copy albums, with only one page crossed out (the quintet, perhaps started before she realized she had more space later in the album), and one unfinished piece (a piano impromptu). The hand is as neat and structured as the pieces themselves; there is no mistaking note pitches or values, and even the spacing is precise. These are manuscripts as much of a performer as of a composer.

There is much written about the handwriting of composers, and what we gain from seeing a manuscript, not just in terms of the controversial idea of “score fidelity”, but from what it might tell us of the composer herself. This, of course, intrigues me too, but even more does it draw me into imagining the composer in the act of writing. Where does she sit, in what room, and at what kind of writing table? How is she dressed? What kind of pen does she use? Who brings her tea, or does she not allow interruptions?

Agnes Zimmermann particularly fascinates me. This is partly because I have been musing on the ways in which women braid together the many parts of their lives, the chosen and the imposed. Perhaps it’s an outcome of having just had one of the two Mother’s Days in my year – living in the UK, my own Mother’s Day is March’s Mothering Sunday, but I ring my Kiwi mum on the first Sunday in May. Zimmermann had many threads in her own personal braid (an apt description, I feel, given the complex and wonderful hairstyle she usually wore), and I wonder how these worked for her – who facilitated which ones, and in what ways. In a world where women were expected to follow well-trodden paths, what was it physically like to choose paths with, as yet, only a few light scuffmarks from female feet? This is a question I will be pursuing in months to come, but it does colour how I listen to this month’s recording, of her three violin sonatas.

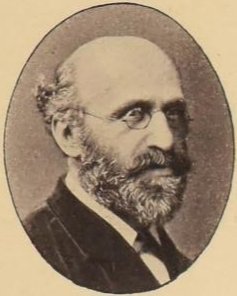

The CD, with Mathilde Milwidsky on violin and Sam Hayward on piano, was released in 2020. Coincidentally this is the same year as the release of a CD featuring Zimmermann’s piano trio, which appeared on a CD with trios by two other nineteenth-century women, Clara Schumann and Louisa le Beau. The three violin sonatas were written between 1868 and 1879, in the first few years after Zimmermann completed her studies at the Royal Academy of Music. She was already known as a proponent of an “old” style that favoured form and clarity; her piano repertoire was centred on Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, though new composers such as Robert Schumann, and her own works, also featured. Reviews often mentioned a “cleanness” to her playing, a word that certainly conjures a particular way of playing (and produced an interesting debate in an undergraduate aesthetics class recently, after reading a review of a contemporary violinist). The same focus is evident in contemporary reviews of her compositions, albeit often implicitly. These two reviews are from 1869 and 1875, when Zimmermann premiered the first two sonatas, the first with Josef Joachim the dedicatee at Hannover Square Rooms, and the second with Ludwig Straus at St James Hall in London.. The first review, of course, cannot resist highlighting the sex of the composer, but the second is more music-focussed:

“The highly talented bénéficiaire, no less remarkable as composer than as pianiste, brought forward a sonata in D minor for piano and violin which in many respects a noteworthy work. The themes, both elegant and characteristic in themselves, are worked with great skill; and, as the fair sex have seldom excelled in musical composition, Miss Zimmermann is the more entitled to praise for the success which has crowned her efforts.

This work is cleverly written, and contains many fine ideas; it is in full proportions, and includes an allegro assai, scherzo, andante cantabile, and allegro grazioso, of which movements we are inclined to give preference to the second. A sonata so ably contrived and abounding in effective passages for both instruments is decidedly worthy of hearing, and we were glad to see Miss Zimmermann bring it forward. ”

Zimmermann never used a programmatic title; all her instrumental manuscripts are neatly labelled as form (Sonata, Fugue), or ensemble (Quartet, Quintet), with the exception of one piano solo, titled “Erzählungen No. 1”. Thus, her violin sonatas follow a lifelong tradition. All are four-movement works, following the allegro-scherzo-andante-finale structure, although in the third, the middle two movements are reversed. The key relationships, too, follow the classical cycle of D-A-G minors, the exact opposite of Brahms’s later set of three in the major. And it’s worth noting that this duo chooses to record in reverse sequence, thus mirroring the more well-known Brahms even more closely. The Tierce de Picardie of the third sonata only serves to highlight this cyclical feel.

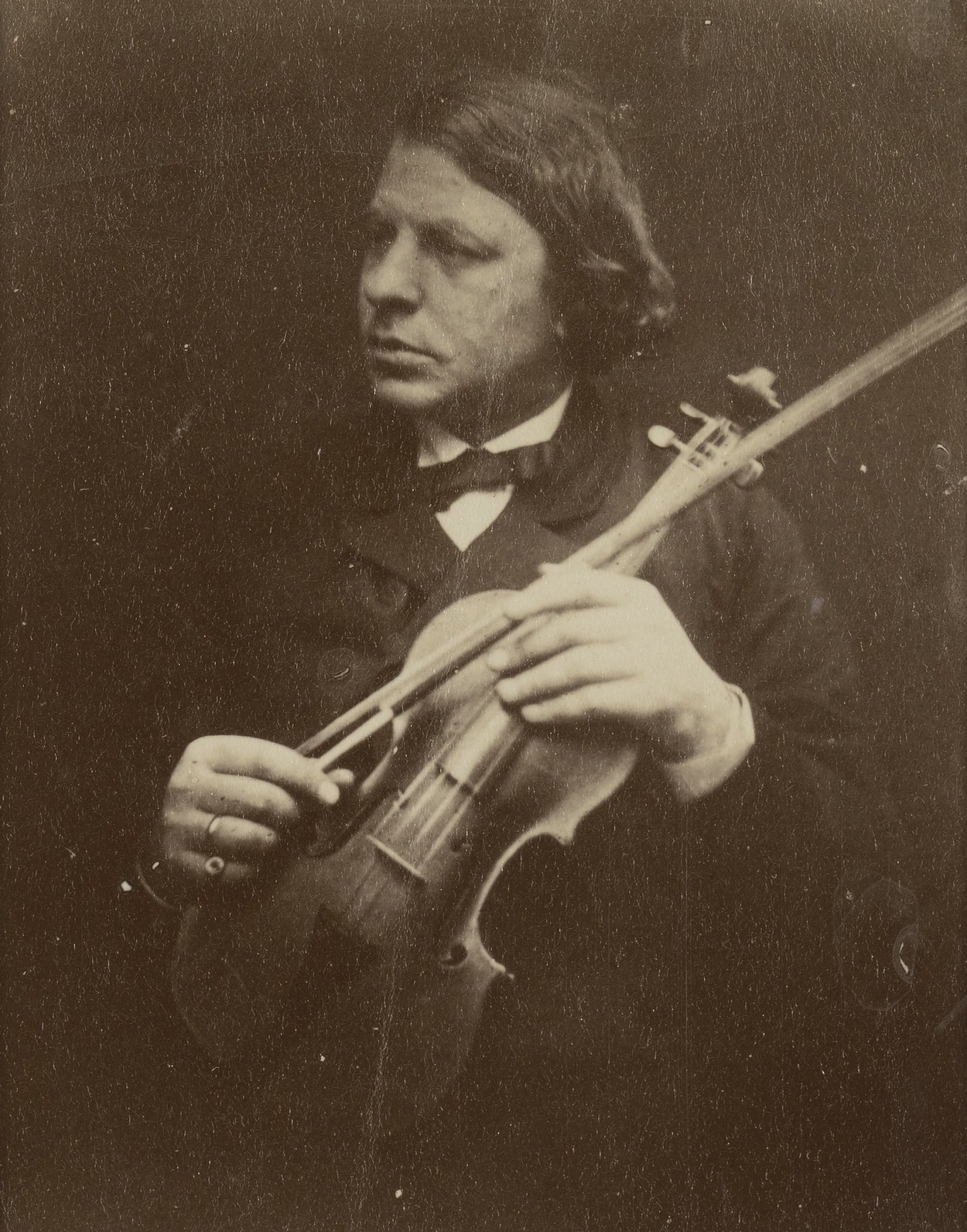

Zimmermann was a frequent chamber musician, playing with many renowned instrumentalists and singers. Alfredo Piatti and Josef Joachim. (Joachim is an interesting figure re women composers, playing works such as Zimmermann’s sonatas, and perhaps most memorably, quoting a song by Bettina von Arnim in the first movement of his third violin concerto.) Her writing for both piano and violin are idiomatic, as well as equal voices in the texture; this is true chamber music. The sense of space that springs off the pages of her manuscript is embodied in the music itself. The realisation that as performers you’re following in the footsteps of Zimmermann and Joachim must be daunting, but the Milwidsky-Hayward duo rise to the occasion.

In a way, there are no surprises here. We tend to confuse originality with innovation, and allow the latter dominance in our hierarchy of artistry. This is one reason why performers get lost into the mists of time – it’s harder to prove an innovative approach to an already-existing set of notes. Zimmermann does not innovate in either form or content, but there is no denying that this is an original voice, with much to say. I hope this is the first of many more performances.

Here is the 1879 reviewer’s favourite movement of the second sonata, the scherzo.