19C RAM Singers on Stage and Platform

In looking through playbills and reviews of the UK musical scene in the mid- to late nineteenth century, it always amazes me just how often names connected with RAM crop up. Of course, given that the Academy was until 1882 the only college in the country turning out professional performers, it’s not entirely to be wondered at; but this is also testament not just to the performers themselves, but to the extraordinary teachers that the institution managed to procure throughout even the first decades of its existence.

I’ve written before about just how many women at this time were able to earn a living through music, most through piano and/or singing (organ came only slightly later). From mid-century, being a former student of the Academy certainly became a selling point in the many advertisements for teaching services. There was often mention in these of specific teachers as well, demonstrating just how much these musicians were household names.

Many women also became performers, both nationally and internationally. One of the first, in just the second intake of students, was Fanny Dickens (1810-1848), whose career was cut short by her early death from tuberculosis at the age of 38. She had been known throughout the UK especially for the concerts she gave with her husband Henry Burnett, also a singer. (It might be added here that it can be quite difficult to unearth anything about Fanny – a search of archives tends to produce results pertaining to her younger brother, who wrote some books.) Two years after the beginning of Dickens’s studentship came Anna Bishop, who has already featured on this website. She was one of the most-travelled singers of the nineteenth century, sallying forth on horse cart, train, ship, or whatever mode of transport would get her to where she was going, on any continent or island. But more importantly, she was clearly a singer of wide-ranging talents, with a repertoire that encompassed opera and concert works from Balfe and Bishop (her first husband) to Handel, Mozart and Beethoven, to Italian composers such as Donizetti and Bellini. Bishop was contemporaneous with the rather less flamboyant but equally successful Mary Shaw (1814-1876), contralto advocate of both Rossini and the modern composer Giuseppe Verdi. She was another singer who benefitted from Mendelssohn’s enthusiasm for British singers, appearing at the Leipzig Gewandhaus several times.

The 1830s began with the admission of such figures as Charlotte Birch (c1815-1901). Active particularly on the oratorio circuit, she entered seven years before her younger sister Eliza Ann (1825-1862), for whom she was the recommender. Charlotte was more in demand than her entry in the 1900 edition of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians intimated:

“Miss Birch possessed a beautiful soprano voice, rich, clear, and mellow, and was a good musician, but her extremely cold and inanimate manner and want of dramatic feeling greatly marred the effect of her singing.”

Sadly, her career was cut short by encroaching deafness, though she remained living with her sister, as so many women of this time did, teaching singing from their residence in Baker Street. Eliza roamed further afield, travelling to other cities to give occasional classes and masterclasses.

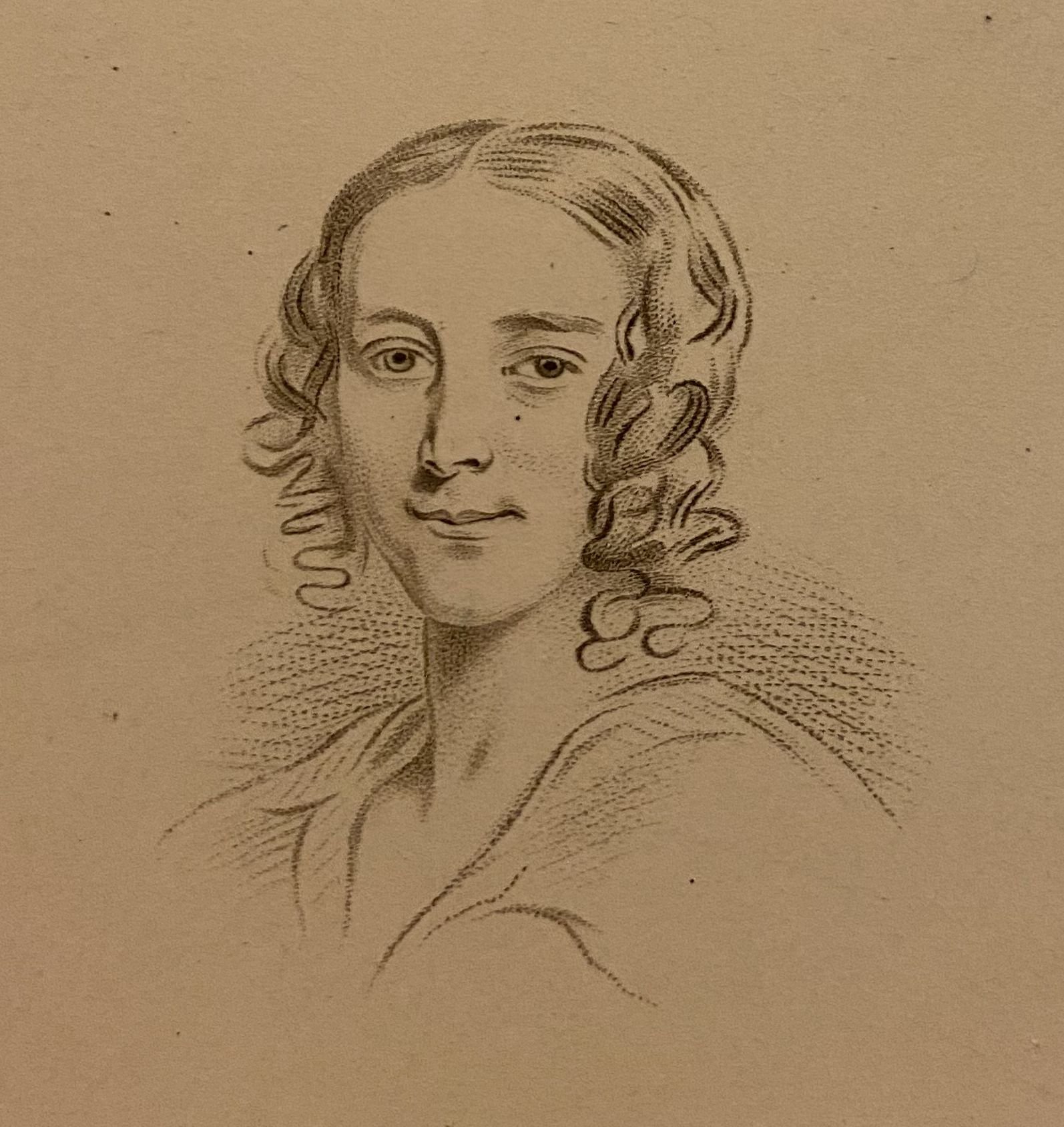

Charlotte Dolby 1821-1885 was another famous figure well into the later century, and has also been a highlight of these pages, over on Composer of the Month. Like many of the singers mentioned above, her singing career gave way to other enterprises in later life, though her name remained a drawcard for her pupils.

By the 1860s, female students far outnumbered male, and the proliferation of successful musicians amongst their numbers continued apace. Singers such as Edith Wynne,

Mary Davies, Rebecca Jewell and Arabella Smyth, to name but a few, made their name both within the walls of the Academy and on concert platforms throughout the country. Next month we will look at the change in instrument availability that resulted in a much broader impact for women in the profession.

Oboe and trumpet, anyone?…