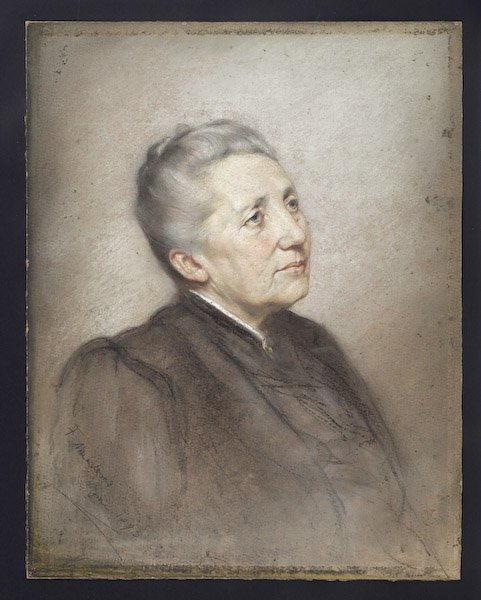

Florence Ashton Marshall 1843-1922

For a woman quite as renowned as Ashton Marshall was in her lifetime, it is remarkably difficult to unravel the story of her life. This is partly because she shares a name with other musicians (including a 15 year old Florence Marshall who thrilled audiences with her pianistic skills in 1888), and partly because she appears to have gone by several versions/combinations of her own name. Still, persistence and faith eventually uncover some of the story of a musician with a wide influence, from young learners to professional performers, composers and researchers.

Marshall does get a Wikipedia entry of her own, scant though it is on detail. One of at least three girls, she was born on 30 March 1843 in Rome, where her father, Reverend J. Thomas, Canon of Canterbury, was based at the time. Little has been written about her early musical life, most of which in any case seems to have happened after her marriage to Julian Marshall on 7 October 1864. (You will be thrilled to know that she “was attended by six bridesmaids, [and] wore a dress of white glacé silk, with white veil and a wreath of orange blossom.”) Although Julian was not a professional musician – he joined the family flax business as a young man – he had a deep love of and interest in music that resulted in one of the largest score and manuscript collections of the nineteenth century. This must surely have been in part influenced by Ashton Marshall, particularly in the Handel specialism of the collection. Both Florence and Julian were prolific writers, contributing articles to the early editions of the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, and also branching out into their other interests. Included in Ashton Marshall’s output is a biography of Handel, and a biographical edition of the letters of Mary Wollstonecraft. Not only this, she also translated from other languages into English, including Spohr’s Violin School from the German. It’s a wonderfully broad array of writing, and with Julian’s forays into the histories of tennis and art, it must have been a stimulating household in which to live. No wonder one of their three daughters, Dorothy Marshall, became a well-known and influential scientist.

In the first decade of her marriage, Ashton Marshall built a successful career as a singer. A mezzo-soprano, she organised many of her own “musical entertainments” around London, enlisting other artists both well-known and new to the stage. Reviews from the early 1870s show that she herself was relatively new to the circuit:

“The fair concert giver, resplendent in a costume which evidently excited the envy and admiration of all the ladies among the audience, and with fair success Tito Mattei’s rather dull song “Non Torno,” and Randegger’s Barcarolle. The young lady has a mezzo-soprano voice which she seems to be endeavouring to train into a contralto. Whether she will succeed in the experiment remains to be proved, but we would caution her not to force her voice. If Nature has fair play we see no reason why Miss Florence Ashton should not become a popular singer. ”

By the time Marshall was approaching her thirties, she was well-ensconced in the London music scene. She had published some songs already, was performing regularly, and was part of the educational efforts of John Hullah, a proponent of class-singing as a method of musical instruction.

Hullah was her sponsor for entry to the Royal Academy of Music in February 1874 at the surprisingly late age of 30. Her main study is listed as harmony, suggesting that despite her background as a singer, her interest already lay in composition. She studied with two principals, William Sterndale Bennett, and on his retirement with George Alexander MacFarren, as well as organist John Goss. Although it is not clear when Ashton Marshall left the Academy, the mention of the award of a bronze medal suggests a year’s study.

Ashton Marshall’s career had many strands. She remained a prolific composer, writing works from symphonies to much vocal music, both choral and solo, to pedagogical works. One such instruction manual was the 70 Solfeggi exercises she published in 1885, the introduction to which demonstrates something of her musical aesthetic:

“These little Solfeggi, written at different times for my own pupils, are the outcome of a wish to familiarise children, as early as possible, with the practical features of Choral Concerted Music, on a scale suited to childish faculties.

To musical natures this working-together in music is a perpetual source of the purest joy, and of an ever-increasing capability for such joy which grows and expands with the musical powers. And it is in childhood, the age of growth and expansion, that this pure source of growing joy should be revealed. ”

Ashton Marshall also contributed part-songs to the popular Novello series and published many solo songs. She turned her hand to transcription of composers such as Mozart and Cimarosa, arranging works for string orchestra. Perhaps the most successful of her works, however, was the last of her three operettas, Prince Sprite. Written in 1891 on a libretto arranged from Countess D'Aulnoy's fairytale Le Prince Lutin by Bertha Thomas, this is scored for treble voices, having been written during Ashton Marshall’s time at Dulwich High School, where she was Head of Music. It gained immediate success, resulting in publication not only of the vocal score, but of the most popular parts (the choral dances were a particular favourite with the public), and performances continued well into the twentieth century.

“The libretto of this charming little work has been arranged from the fairy tale of the Countess D’Aulnoy by Miss Bertha Thomas with no little skill. The story has, we believe, been dramatized before under the title of “The Invisible Prince”; but the present version derives no little of its attractiveness from the simple yet graceful music with which it is associated. There is a bright overture for four hands, with violin ad lib., and fifteen other numbers – choruses, duets, songs and instrumental pieces, including some graceful soft music, and some excellent dance measures. The vocal parts are well written, and show considerable knowledge of vocal effect and no little skill in writing for treble voices, so that it should command a welcome from those choral societies where female voices only are available for its utility in that respect. Its musical qualifications will be certain to secure favour for it wherever it is known.”

Teaching remained an important part of Ashton Marshall’s life, leading to the foundation of the Hampstead Conservatoire, a music school that grew large enough to require a full board of directors, and which boasted two orchestras and a choir alongside classes and lessons. Ashton Marshall conducted both orchestras; and outside the conservatoire, was also chief conductor of the South Hampstead Orchestra. This was clearly an excellent orchestra, a mix of amateur and professional musicians, which attracted soloists of the calibre of Fritz Kreisler, Isolde Menges and Mischa Elman. Many of the concerts took place in St James Hall, London’s premier concert hall in the second half of the nineteenth century and home to the Philharmonic Society, of which Ashton Marshall had been made an associate member. She would remain their conductor until around 1920, acquiring a raft of positive reviews for both the orchestral playing itself and for her own conducting.

Florence Ashton Marshall remained active in the British music scene until her death on 5 March 1922. An interesting side note is her inheritance in 1894 of the vast sum of £10,000 from an uncle who had made a fortune on the railways; this allowed both wife and husband to draw back from earning a living and concentrate on their musical and other passions. The obituary in The Times paid tribute to her extensive influence:

“Up to the time of the war Mrs. Julian Marshall, who died in London on Sunday at the age of 79, had been a very well-known figure in the musical life of London. For close on 30 years she had conducted the South Hampstead Orchestra, an excellent amateur institution, which gave occasional concerts in the centre of London, latterly at Queen’s Hall. When she began this work the fact of a woman conducting a full orchestra at all was sufficiently unusual to excite remark, but Mrs. Marshall was the last person to wish to found a reputation on the sex qualification. She was a genuine musician who knew what was good and was determined to give it in the best possible way. Musicians were attracted to her concerts because they found there, played with intelligence and care, works which were often passed over by the more commercial institutions. In particular Mrs. Marshall gave some notable performances of the symphonies of Brahms at a time when they were not considered to be the popular attractions they are to-day. She secured the cooperation of the most eminent solo artists, such as Kreisler and Casals, and their performances of concertos with her, who so well understood the art of orchestral accompaniment, will long be remembered.”