Una Mabel Bourne 1882-1974

I have a long-held fascination with women pianist-composers of the early twentieth-century, particularly British ones, who have tended to lie forgotten at the bottom of the undeniably impressive mountain of virtuosi who succeeded them. Many had successful careers as soloists and sought-after collaborative pianists, appearing on platforms globally as well as being instrumental in the early days of recording and radio.

Una Bourne is one of these. I first came across the name of this Australian pianist several years ago, in a search for recordings of Chaminade’s Études de Concert. At the time of my search, Bourne’s recording of the third, Fileuse, was the only one I could find. Her crystalline, impeccable playing immediately captured my attention. Underneath the surface crackle of the 1914 recording was the sound of an extraordinary musician. I had other pressing research requirements at the time, so it was some months before I encountered her again, this time as the ensemble partner of the equally exciting and fascinating violinist Marjorie Hayward. And in the ensuing YouTube list of Bourne’s recordings, I discovered that she was also a composer. It was time, I decided, to find out more about Bourne.

Una Mabel Bourne was born in New South Wales to a shopkeeper’s family. Somehow, her talent as a musician was recognized early; there are several stories about her early study at the piano, all revolving around her older sister. These range from a brief note that the young Una was sent to study with her sister Margaret, who no longer lived at home; a more picturesque version comes from the Dominion newspaper in New Zealand, which wrote in 1909:

“When she was a tiny child with a delicate mother, her sister, who was devoted to music, had to take the baby in her care, and, in order to go on with her practicing and yet keep guard over the child, she used to strap her in a chair and draw the chair close up to the piano, where she soon found that the little one would be “as good as gold”. In a very short time, from listening, the child began to play at the treble end of the piano, harmonizing with whatever her sister played.”

It seems clear at least that Margaret was indeed her teacher for the first few years, and that she was clearly good at her job, nurturing the little Una as both pianist and composer. Una did well in her first public appearances. A report of “an amateur music contest” in 1894 was fulsome in its praise:

“Class 1 (pianoforte, under 13) and Class 2 (pianoforte, under 18), both won by Miss Una Mabel Bourne. This last-mentioned double winner is a small child only 11 years old, and, as far as her performance of Beethoven’s “Moonlight” sonata was concerned, one of the most remarkable instances of a matured head upon young shoulders that I ever remember. With the exception of one or two mistaken readings-for which not she, but her teacher, must have been responsible-she played with unerring accuracy, and the musicianly instinct and comprehension of the composer’s intentions that were truly astonishing in one so young, and point the way to a great and distinguished future-provided, of course, that her musical education is entrusted to some reliable and well-recognised authority. It will be watched with keen interest.”

Soon after this, Bourne began studying with the Polish-born pianist, conductor and impresario Benno Scherek. PIC She remained with him for five years, performing with his orchestra in repertoire such as the Robert Schumann and Anton Rubinstein concertos and Liszt’s Hungarian Fantasia, all, to the wonder of local reviewers, before the age of 18. In 1905 she headed off to Europe for further study, visiting Germany, Austria, France and the UK and taking lessons with teachers in several cities there. This first 18-month sojourn in Europe culminated in a recital at Bechstein Hall on 6 October 1906, alongside the soprano Mona McCaughey, who would become a lifelong partner and musical collaborator. Reviews were positive: “Miss Bourne showed fluency and power of expression, while Miss McCaughey’s songs from Der Freischütz Lorlei, &c., were deservedly much applauded.”

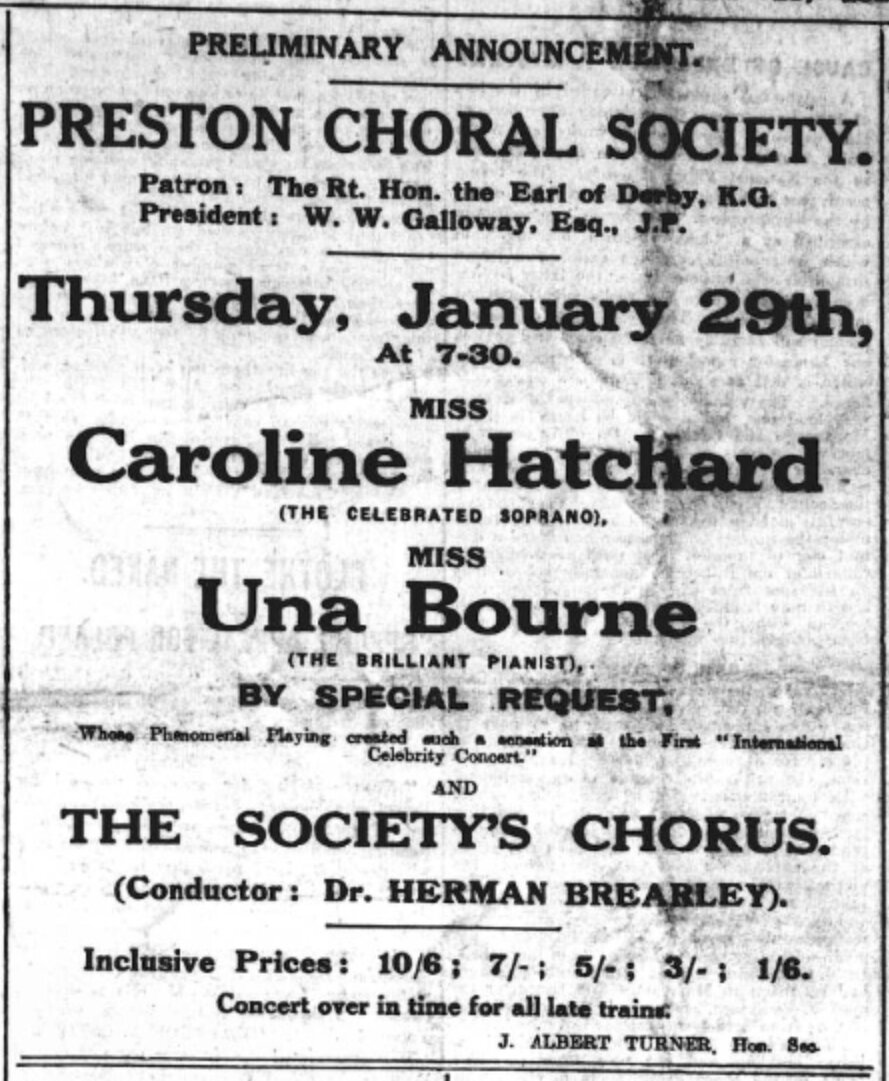

From this point, Bourne would spend much of her musical life traversing the globe between the UK and Australia. In large part this was thanks to the globally-famous soprano Nellie Melba, who selected her in 1907 as a contributing artist to her concerts far and near, a relationship that would last until Melba’s retirement in 1926. Although Bourne sometimes accompanied the singer, mostly she played solos (this being still the era of the variety concert). With Melba, she toured many countries, from Europe to New Zealand. The reviews were uniformly impressive, and soon she began to be billed with labels such as “The brilliant pianist” and “Australia’s premiere pianist” on the advertising.

Bourne remained in England during World War I, giving charity concerts for civilians and soldiers, including in hospitals, a service she repeated in World War II in Australia. She also began her long association with the English Gramophone Co., recording over 80 works, both solo and ensemble. Her catalogue includes several pieces by Chaminade – including the aforementioned Fileuse – and some of her own compositions, some of which formed the first recording she made in 1914. Her clarity and sparkling tone suited the early recording equipment, and her recordings became widely popular. As one 1923 review observed, “Una Bourne is another pianist whose touch seems to suit the gramophone. Her neat execution of the ‘Six Cuban Dances,’ by Cervantes, should please everybody.” Bourne also became one of the recording partners of violinist Marjorie Hayward, in repertoire that included Beethoven’s Kreutzer Sonata and Cesar Franck’s sonata, both of these abridged to fit on a 78. For reviewers, the two players were “a happy combination,” as one 1926 review described their Mozart performance, while the Grieg also was well-received:

“On three 12-inch records […] we have Grieg’s lovely Violin Sonata in C Minor, played by Marjorie Hayward (violin) and Una Bourne (piano). To music-lovers it will be a welcome fact that this captivating work can be obtained so delightfully performed and excellently recorded […] Miss Hayward and Miss Bourne are performers whose artistic skills can be depended upon to give a virile rendering, and for anyone who wishes to have records of music which can give him many hours of increasing pleasure, these three discs are to be recommended. (1928)”

(And I am sure you have all spotted the approvingly masculinised performance, something that comes up time and again for both players. That, however, must be a separate post.)

Bourne visited America in 1924 on a return journey from England to Australia. Her she recorded several Duo-Art piano rolls, including Brahms waltzes, a Beethoven sonata, and a piece by Selim Palmgren, who featured often in her concert repertoire.

As with many pianists of her time, Bourne’s own compositions appeared in her concert repertoire for early on, and as previously mentioned, were the first pieces she recorded. She appears to have begun publishing these during WWI, the Nocturne and Cradle Song being published in Australia by Allen & Co. Bourne clearly was not contracted to a specific publisher, and both first editions and reprints appear under a variety of labels, both in Australia and the UK. Her works are all piano miniatures, although there are two cycles – In Mother’s Garden, and Days of Old. There is a real correlation between these pieces and Bourne’s playing, demonstrating a clear set of underlying musical principles. It is easy to muddy the waters of pieces such as Marche Grotesque, which starts so low on the keyboard, or Cradle Song, with its semiquaver triplet flourishes that can seem contrary to the implied serenity of the title, and only a touch like Bourne’s can make them sing as they should. Bourne appears to have ceased composing fairly early; the last pieces to be published, in 1928, were two sets of Schubert dances arranged by Bourne for solo piano.

In 1939, with war looming again, Bourne returned once more to Australia, which would become her base for the remainder of her life. She taught at the Albert Street Conservatorium from 1942, where she developed the pianists’ course, while also working in broadcasting (she was one of the few women to be on the advisory committee of the Australian Broadcasting Commission), and giving concerts throughout Australasia. From this point she was living with her singer-partner Mona McCaughey. McCaughey died ten years before Bourne, and when Bourne herself died, she left an endowment for the “Mona McCaughey Scholarship – Una Bourne”, which is still offered to piano students at the School of Music and Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne.

You can hear Una Bourne playing her Marche Grotesque here.